Theresa May's “three principles” raise serious concerns about the UK’s response to the global refugee crisis

Every year 193 world leaders descend on New York for the annual UN General Assembly meeting. This year they will use this opportunity to discuss the global response to the current refugee crisis.

The UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants, which started on Monday, claims to be bringing states together to devise a humane response to the crisis. It is worrying that even before the Summit had started, the Prime Minister announced “three principles” that raise serious concerns about the UK’s role in that global response.

The Prime Minister’s principle of a “first safe country”, insisting refugees should only claim asylum, and by implication stay in, the first safe country they reach, is of course consistent with the Dublin Regulation, and the government’s previous announcements of increased support to regional neighbours such as Jordan and Lebanon who are hosting millions of displaced Syrians. But we have already seen that this system fails refugees. Resources and support mechanisms are underfunded and stretched. Vulnerable people feel they have to continue their journey to find some form of safety. Numerous Syria Pledging Conferences have failed to generate the funding to make sure that regional camps have enough shelter, food, water, school places for children or healthcare. The newspapers carry horrific stories of the conditions faced by refugees forced to live in makeshift camps in Greece and France. Before she even arrived in the UN building, the Prime Minister is sending a message that it is someone else’s responsibility to provide sanctuary and support to people are fleeing for their safety.

The Prime Minister’s principle of a “first safe country”, insisting refugees should only claim asylum, and by implication stay in, the first safe country they reach, is of course consistent with the Dublin Regulation, and the government’s previous announcements of increased support to regional neighbours such as Jordan and Lebanon who are hosting millions of displaced Syrians. But we have already seen that this system fails refugees. Resources and support mechanisms are underfunded and stretched.

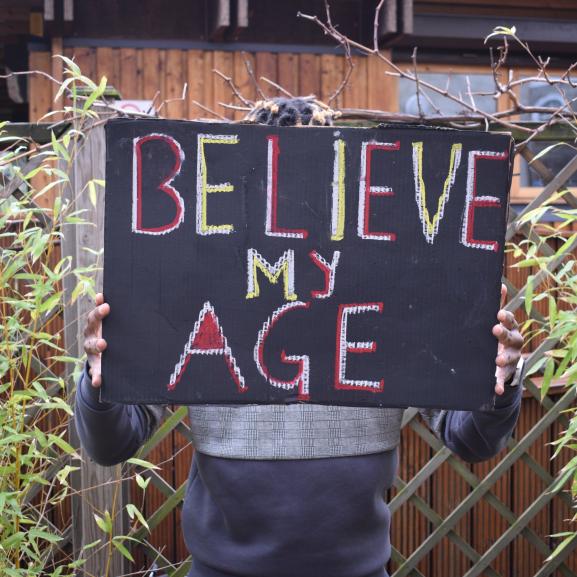

May’s second principle emphasises the need to distinguish between refugees and economic migrants. We know, from the people who come to Freedom from Torture that while they are displaced and desperately seeking safety, this is the time that they are least able to make an effective case about what has happened to them. It can take weeks, months or years for a traumatised survivor to disclose their torture. There is a risk that a process which tries to categorise people earlier will disproportionately harm the most vulnerable.

Lastly, the Prime Minister’s final principle, emphasises the right of countries to control their borders. This only perpetuates the racist myth that we should be fearful of refugees, demonising individuals who have been forced to abandon their home countries and are the victims of circumstances way beyond their control. While the safety and security of our nation is paramount, it should not be to the detriment of the vulnerability of human beings, many of whom have escaped horrific psychological and physical torture and have come to the UK as deeply traumatised survivors seeking refuge.

Equating refugees with a security threat undermines the community integration that is meant to be at the heart of schemes such as the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Programme.