What is the future of accountability in Sri Lanka?

by Ann Hannah, Acting Director of Policy and Advocacy at Freedom from Torture

I know from working with torture survivors in our centres around the country that accountability can mean different things to different people. In Sri Lanka accountability appears to mean very little to the government. Worryingly, it also seems to be seen as dispensable by Sri Lanka’s international friends and partners where it is being claimed it is incompatible with the political situation and economic development.

Ever since Human Rights Council Resolution 30/1, co-sponsored by the Sri Lankan government, was agreed in 2015 that same government has said and done little on accountability for past human rights abuses. Progress has also stalled on most other areas of the transitional justice process which aimed to help Sri Lanka move away from the devastating impact of the long civil war towards a peaceful, inclusive future.

At Freedom from Torture, we continue to document torture taking place under the current government. the growing silence around accountability causes us huge concern but more importantly it sends a demoralising message to the survivors we see in our services.

Sadly, Sri Lanka is still our top country of origin for referrals of torture survivors. Reports of abuses happening now undermine the fragile paper-thin trust in the government to ensure that their torture won’t be repeated.

Culture of impunity

We have reported extensively on torture in Sri Lanka after the end of the conflict in 2009 and since the change of government in 2015. Sadly, we are still seeing clients who report recent torture linked to real or perceived links to LTTE including interrogation about resurgence of the group and/or weapons stashes.

The vast majority of them do not fit the Home Office’s profile of those who are at risk of coming to the attention of the authorities and our reports have highlighted interrogation and torture of people returning to Sri Lanka from the UK who are shown pictures of themselves at legal protests, commemorations or other activities in the UK.

We are concerned that failure to address past abuses contributes to ongoing torture. There is a culture of impunity that has very few structures in place to challenge it, coupled by at best ambiguous political messaging about investigations and justice for past abuses.

At worst, there are attempts to discredit the organisations including Freedom from Torture, who document torture and support survivors.

The structures that support torture need significant political and practical investment in reform. We know that there is some work in progress with these structures and of course, reform of any system takes time and patience but there is a lack of transparency about what emphasis is being given to elements such as torture prevention in these programmes.

The UK government, for example, is supporting capacity building with various units of the Sri Lankan police and we know has in the past explored options for defence engagement but there is very little information available about how they are addressing torture prevention. Sri Lankan engagement with these initiatives may be excellent – we don’t know and therefore survivors also do not know.

More has to be done to tackle this culture of impunity – concern about ongoing security threats never justify torture and there is a risk that mistreatment will contribute to the very thing the authorities worry about.

What does accountability mean to survivors?

The need for accountability is underlined by incidents such as the recent threatening behaviour of the Sri Lankan defence attaché in London. A number of our therapists told us how distressing some of our clients found this incident.

In 2016 we worked with a group of Tamil torture survivors who are in treatment with us to discuss what accountability means to them and what they want to see from any process. I have highlighted three of their points here:

1. They all said that they want to see accountability because they want to stop the abuse that happened to them happening to others.

2. They shared a belief that any process has to send a message that these abuses will no longer be tolerated.

3. Their final point was that they want recognition (particularly for abuses around and immediately after 2009) on both sides of what happened so that it can contribute to a balanced political conversation about the future of the country and the mechanisms that need to be in place to maintain peace and security.

This final point in particular should be of concern to everyone who has played a role in ending the conflict in Sri Lanka – including the Human Rights Council. It is short-termist to think that not dealing with accountability now will create longer-term political stability. The current threat of the return of the Rajapaksa dynasty is a worrying development, given the human rights abuses that that took place between 2009 and 2015.

The future of accountability?

If we are serious about sending a message that torture and other human rights abuses are unacceptable in Sri Lanka then we must to continue to demand that those responsible are investigated and held to account.

Accountability and reform need long-term engagement. At the All Party Parliamentary Group on Tamils event in the House of Commons on Monday, the chair Paul Scully MP, talked about the UK being a critical friend. We welcome that sentiment but would urge that the UK makes sure it’s criticism and friendship are both consistent and public. It is clear that the Sri Lankan government needs more support and pressure to start taking this issue seriously.

We believe that Sri Lanka needs its critical friends now more than ever and would call on them to:

- Focus on torture prevention in programme engagement and transparency about work being done in this area.

- Support calls for the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to engage with the evidence of torture from 2015 onwards.

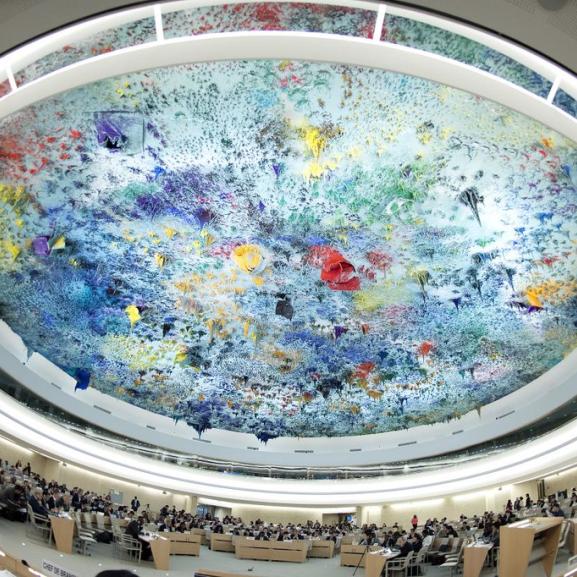

- A renewed focus from the Human Rights Council for the government of Sri Lanka to deliver fully on the commitments it made in 2015 - including those on accountability.

Ann Hannah spoke on this subject at a joint event by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Tamils and the International Truth and Justice Project at the Houses of Parliament on 23 April 2013.