Bearing witness: John McCarthy explains why Freedom from Torture's work is more important now than ever

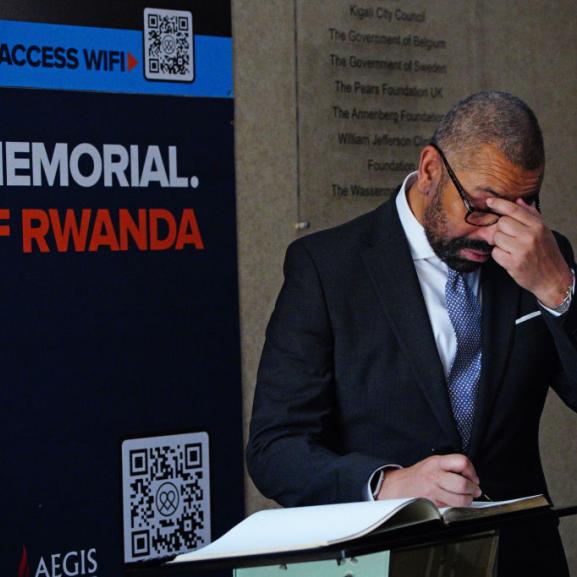

Following his experiences as a hostage in Lebanon, the author and broadcaster John McCarthy became a patron of Freedom from Torture. He recently joined us at Downing Street to hand in a petition calling on Prime Minister Theresa May to reaffirm the UK’s commitment to the absolute ban on torture, and here explains why our campaigning work is more important now than ever.

My involvement with Freedom from Torture began within a year of my coming back from Lebanon in 1991. I was still coming to terms with being widely recognised, with lots of people coming up to me and saying “Welcome home, I can’t imagine what it was like”. I got used to having a fairly simple answer to these sympathetic comments.

My fellow hostage Brian Keenan published a book about our experiences, with the launch hosted at what was then the Medical Foundation’s offices. I remember speaking to Perico Rodriguez, one of the founding members of Freedom from Torture: he didn’t say “I can’t imagine what it was like”, he just asked me how I was.

I suddenly realised that many of the people around me knew exactly what Brian and I had been through, either as counsellors through listening to others, or because like Perico they were survivors themselves. I understood that I was talking to people who weren’t just being sympathetic and friendly, they really did understand very profoundly what we’d experienced, and what it was like to come out of captivity. It was an extraordinary moment.

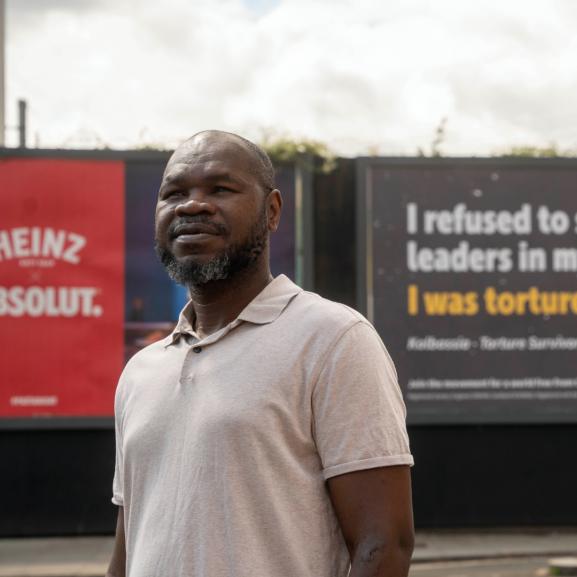

It truly felt like coming home. I was surrounded by all these people from different parts of the world: I was a survivor like them, but I also saw how much harder it was for them to be living in exile, having been forced to leave their homes, their families and their communities because of the torture they were put through.

Throughout my time working with and supporting Freedom from Torture, I’ve been particularly inspired by two aspects of our work. The first is, obviously, the hands-on counselling, care and support for survivors, whether they’ve been in the UK for a number of years or they’ve just arrived.

What’s particularly impressed me is the imaginative way that that Freedom from Torture approaches therapy: survivors speak to their therapists one to one, of course, but also access group activities like the children’s group, the gardening group or breadmaking. I made a radio programme about what an extraordinary idea this is: getting people to talk about their experiences and their feelings in a contained space, somewhere that gives them the opportunity to talk freely without their emotions being the sole focus. That immediate, caring side of Freedom from Torture’s work is hugely important.

With Trump in power in the US and Britain leaving the EU, there seems to be a feeling of attention turning inward, of society becoming increasingly selfish, obsessed with getting a good financial deal whatever the cost. In doing so, we risk turning a blind eye to the more troubling aspects of certain countries’ behaviour as we end up depending on them, regardless of whether or not they share our concerns about human rights.

The other aspect which remains absolutely vital is our campaigning work, particularly thinking about last week’s petition and our new research report on Iran. My liberation from captivity in Lebanon came at a time when the Middle East seemed to be changing for the good: the Cold War had ended, and relations with countries there were improving dramatically. In 2017, we now look at the UK engaging with those same regimes, whether it’s Iran in particular or other countries which use torture or political repression, and wonder whether the government’s attention on promoting democracy and human rights is slipping.

With Trump in power in the US and Britain leaving the EU, there seems to be a feeling of attention turning inward, of society becoming increasingly selfish, obsessed with getting a good financial deal whatever the cost. In doing so, we risk turning a blind eye to the more troubling aspects of certain countries’ behaviour as we end up depending on them, regardless of whether or not they share our concerns about human rights.

In particular in the UK, we should all be deeply concerned that empathy or recognition is too rarely afforded to the suffering experienced by torture survivors and their families. There’s still a huge risk that they’ll be illegally detained, or will be re-traumatised or otherwise harmed by a hostile and uncaring system.

I know from my experience that it can be incredibly harrowing to talk about what happened during torture, and yet survivors still face hostility in proving just how badly they’ve suffered. I had it far easier than Freedom from Torture’s clients: I came home and would happily talk to the authorities in the UK, because I knew they were on my side. But if you’re someone who’s been abused and tortured by the police in your home country, the last person you’re going to open up to is someone in uniform, or wearing the suit of the bureaucrat.

In standing up for their rights and those of their communities, survivors are so often exemplars of what we would want to be. Both in its dealings with other countries and its treatment of survivors in the UK, the government needs to be doing more: we should be holding up a much wider and more caring hand to survivors who desperately need and deserve our help.

Whenever the UK government builds relations with other countries, or makes life harder for survivors within our borders, we have to stand firm, and show that political or economic questions have to be addressed in tandem with protecting or improving human rights. Freedom from Torture’s campaigning work bearing witness to what goes on in various parts of the world is vital: we can act as a conscience and reminder to our leaders that you cannot abandon human rights for self-interest.